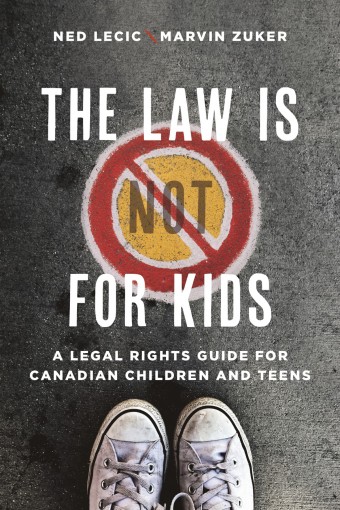

The law is not easy for adults to navigate, let alone for children and teens. However, young people need to be aware of their legal rights.

The Law is (Not) for Kids: A Legal Rights Guide for Canadian Children and Teens is a practical guide to the law, written especially for Canadian youth.

“As a longtime activist researching the legal rights of children and youth, I had always found the exact extent of these rights to be difficult to pinpoint,” co-author Ned Lecic, who is also a copy editor and translator, says.

He says that much of the information available for young readers is incomplete, conflicting, or inaccurate.

Lecic contacted Marvin Zuker to collaborate after remembering the book The Law Is Not for Women, a comprehensive guide to women’s legal rights, which was co-written in the 1970s by Zuker and June Callwood.

- The Law is (Not) for Kids

- Ned Lecic, Marvin Zuker

- Athabasca University Press

- $22.95 Paperback, 204 pages

- ISBN: 978-17-71992-37-4

“I thought it was time that young people were given a similar book that would explain what rights the law gives them and withholds from them clearly and comprehensively, but which also encourages the reader to question the limits that the law and society place on youth,” Lecic says.

Zuker, associate professor at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto, says the book will provide young people with information that many would not otherwise receive.

Outside of some high school law or civics classes, most young people might not have access to “information about their rights and responsibilities, what they can and cannot do (legally), federal and provincial and municipal laws that impact them, things like the social media, et cetera.”

The book also encourages young people to organize and advocate for more legal rights.

“Although there are some opportunities that did not exist in previous generations for youth to participate in decision making, and although there is, for example, less tolerance for child abuse than there used to be, by and large, the attitude of the law and society is still that adults are in charge over young people, even pretty mature ones,” Lecic says.

“It is still often difficult for children to get even their opinions heard and duly taken into account, let alone to make final decisions about matters that affect them (and where they can legally do so, they may not always be told how to go about it).”

And children have the right to express their views and participate in decisions concerning them, according to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

“Children must be respected and given increased autonomy. A child is not a piece of property, and parental rights do not automatically trump rights of the child,” Zuker says.

Children may also need protection. “Young people have the right to be free from all forms of violence. In short, there needs to be a child-based rights approach in law,” he adds.

Lecic hopes to provide children and teens easy access to information on how the law treats them in a wide variety of situations – in the family, at school, at work, and so on.

He also hopes that “young readers will come away as seeing themselves as worthy of having rights and that the book will start a conversation in society at large on the subject of increasing the rights of children and teens.”