Scratching River is unlike most books you’ve read – but if you’re Métis, it might sound a lot like stories you’ve been told.

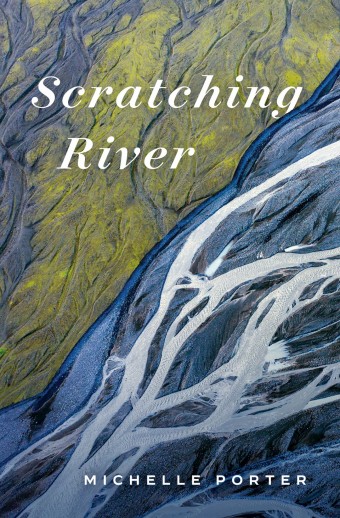

- Scratching River

- Michelle Porter

- Wilfrid Laurier University Press

- $22.99 Paperback, 184 pages

- ISBN: 978-17-71125-44-4

Michelle Porter tells the story of her brother, but that wasn’t her intention when she began writing. She meant to write about her ancestor, Louis Goulet.

“These physical memories of being in a car going to see my brother kept coming up as I was reading Goulet’s very evocative descriptions of travelling various places along the homeland, following the hunt,” Porter said.

“As that opened up the space of my brother, I felt like that 14-year-old girl sat down beside me, and said ‘I have a story to tell.’ And I said ‘OK, I’ll tell it.’”

Porter is Métis and grew up in small towns around Alberta. While she is now working remotely in St John’s, St. Albert still feels like home to her. Her childhood and adolescence were marked by her brother, Brendon, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia and autism and sent to live in care homes as a child.

Despite their physical distance, Porter is close with her brother and describes him as dynamic and effervescent, like a river. This closeness made his experience of abuse at an adult care home – referred to as “the Ranch” – all the more painful. In the process of telling this story, she realized how deep her own wounds ran.

“It never occurred to me that what happened to my brother had not healed for me,” said Porter.

Because Brendon is non-verbal, Porter had to get resourceful to make sure her perception of him didn’t dominate the story. Through Brendon’s “talent for being remembered,” she was able to integrate his caregivers’ memories and conversations with her mother and sister.

“It didn’t become my story, because it isn’t. It’s my sister’s, it’s my mother’s. Through that constellation of voices, you get a little bit more of my brother,” said Porter.

The book weaves several other stories into Brendon’s. It flips back to Louis Goulet’s story, offers snippets of Métis knowledge, and has flashes of vivid prairie imagery, all interspersed with news clippings investigating the abusive Ranch.

“It’s that Métis need to have everything in conversation with everything else. To have everybody in conversation with everybody else,” said Porter.

Scratching River does not necessarily move forward, towards a resolution – rather, it moves in a circle, in conversation with the past, with the present, with memories, with other people, with nature, and ultimately, towards healing.

Braiding bison and rivers into descriptions of her family, Porter reminds us that we are inseparable from our environment, our ancestors, and our loved ones.

Porter realized she didn’t get to witness her brother’s healing from his trauma. Telling this story acted as a healing process for her – and reading it shows that in order to heal, we must embrace connection.

“My brother can’t speak, he is for all intents and purposes someone who can be said to have so many challenges. It’s unbelievable, but he taught me how to move on from trauma. He taught me how to see it, acknowledge it, and gave me the courage to do that,” said Porter.