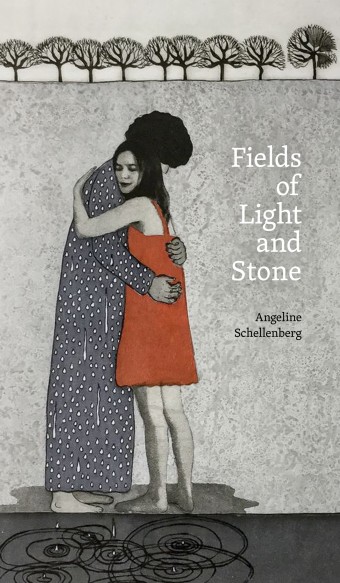

Faith, love, death, displacement – these are the themes Angeline Schellenberg tackles in her new collection of poetry, Fields of Light and Stone.

- Fields of Light and Stone

- Angeline Schellenberg

- The University of Alberta Press

- $19.99 Paperback, 104 pages

- ISBN: 978-17-72125-11-5

These poems tell the stories of her grandparents – Abe and Margaret, and Bernhard and Elsa – with whom Schellenberg was especially close as a child.

“I grew up next door to my dad’s parents; Oma and Opa helped raise me. When everyone else was busy working on the farm, my arthritic Oma could be found in her chair, ready to tell a story to the girl crying over a malicious clarinet or bicycle. And I was my Opa’s ‘Rosebud’; he made me feel precious,” says Schellenberg, who now lives in Winnipeg.

“On my mom’s side, we made the three-hour drive to my grandparents often. Grandpa was a preacher, who (unlike some of my Sunday school teachers) enjoyed my theological interrogations.”

It was because of this close connection that Schellenberg wanted to explore and write about her grandparents’ lives. She used a variety of sources: old pocket calendars, sermon notes, memoirs, and funeral tapes.

“I wanted to imagine how my grandparents’ early experiences – famine, war, loss, abuse, displacement – shaped them into the unbreakable characters I knew, and then how those last holy and agonizing weeks softened them into something more transparent. And, in turn, I wanted to reflect on how their lives and deaths shaped me,” says Schellenberg.

Going through her grandparents’ old materials was a precious experience, especially when it came to reading their love letters. “They sounded like themselves – Grandpa, eloquent and proper; Grandma, playful and considerate – but both more affectionate than they ever were in public,” she says.

These love letters are interspersed throughout the collection to create an “Aha, this again!” experience for readers, but they have also been rearranged so that they don’t respond to the same things they did in the originals.

“When Margaret talks about her father seeking Abe’s release, she meant from CO [conscientious objector] service, but by placing this in the context of Abe’s words about never wanting to let her go, ‘release’ takes on a broader meaning. I did this both to play up their character and to protect their privacy.”

For Schellenberg, the loss of her grandparents was monumental. “When I was 24, [Grandpa’s] death was my first experience of personal loss. Other people wondered at my level of grief and, for the first time, I realized that not everyone is as connected with their grandparents as I was,” she says.

“For the last decade of her life, Grandma moved nearby and became like a second mother. When she died in 2009, it felt like the last of four support beams was knocked out from under me.”

At its core, Schellenberg’s collection is a love letter to these four people whose lives were so completely intertwined with hers.

“In a hospital bed,” she says, “there’s nothing to do but what was essential all along: to be present to one another. I didn’t ever want to forget those moments.”