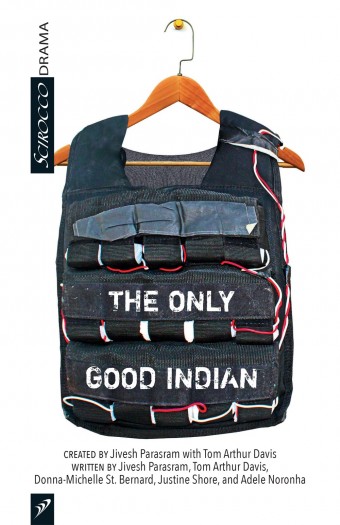

What would it be like to get into the headspace of a suicide bomber? The play The Only Good Indian gives artists the opportunity to find out. For each performance, a different artist straps themself into a suicide vest and then tries to justify carrying out such an extreme action.

- The Only Good Indian

- Tom Arthur Davis, Jivesh Parasram, Donna-Michelle St. Bernard

- J. Gordon Shillingford Publishing

- $15.95 Paperback, 96 pages

- ISBN: 978-19-27922-91-0

The script is part augmented lecture (blending political theory with satire), and part personal narrative, with each artist exploring their own relationships to colonization, occupation, otherness, and Indigeneity.

Five versions of The Only Good Indian by Donna-Michelle St. Bernard, Tom Arthur Davis, Adele Noronha, Jivesh Parasram, and Justine Shore are collected in the book The Only Good Indian.

Co-creator Jivesh Parasram, a Vancouver-based multidisciplinary artist of Indo-Caribbean descent, says writing a piece from the point of view of a suicide bomber was complicated.

“I had no right really to speak from that perspective – and all of my research had pointed to the fact that rationales for suicide bombers were immensely diverse, despite the common depiction in culture and news coverage. The only thing that linked suicide bombers really was that they only tended to act in instances of occupation.”

As a result of that thinking, Parasram, and his co-creator and Pandemic Theatre co-founder Tom Arthur Davis, had two objectives: to diversify the perspective they were presenting, and to engage with the theme of occupation.

“Tom and I worked on the piece with the understanding that we would diversify it by having different performers each night (in theory), which also played a bit with the false reality of the performance, and whether the performer would in fact explode (one night only!),” says Parasram.

They identified key lecture components addressing concepts such as occupation, the word Indian, and objectification. From there, they created writing prompts to help each performer to mine their own heritage/experience.

“It’s always a tricky balance doing socio-politically conscious work. There’s a desire to address systems of oppression and acknowledge those that are affected by those systems. But we also don’t want to perpetuate those systems or be reductive with people’s experiences,” explains Davis, a Toronto-based theatre artist and producer.

“Satire is a dangerous rope to walk. We hope that we’re minimizing any potential violence on the audience by accepting that there are different ways of thinking about the world, which all come together to make up a whole truth, even if these truths are sometimes contradictory.”

While the book contains five versions by five writers/performers who have taken part in the project thus far, publication does not mean finished. “We’re offering the political lectures and the prompts rights-free in the hope that others might create their own events across the country that will have more artists and audiences questioning their roles within occupation,” says Davis.

Parasram hopes readers will use their imaginations to question how they, or people they love, would fit into the narrative. “I want people to be able to, through maybe making their own version, reach through their own history and identify the ways that occupation has impacted their life. Maybe as the occupier, maybe as the occupied. Maybe both. Perhaps even at the same time,” he says.

“To me, this is the kind of nuanced discussion we need to be able to readily enter into.”