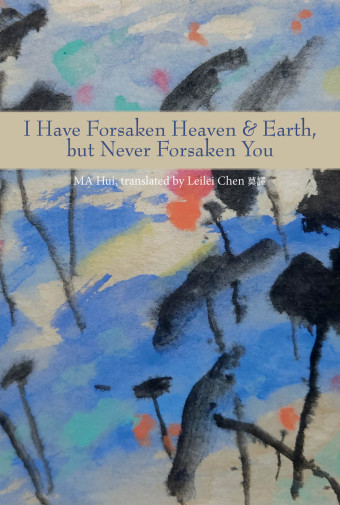

I Have Forsaken Heaven & Earth, but Never Forsaken You is the translation into English by Leilei Chen 莫譯 of the creative reworking by MA Hui of different Mandarin translations of the poetry of Tibet’s sixth Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso (1683–1706).

- I Have Forsaken Heaven & Earth, but Never Forsaken You

- MA Hui, Leilei Chen 莫譯 (Translator)

- Frontenac House Ltd.

- $19.95 pb, 96 pages

- ISBN: 978-1-989466-64-3

Edmonton-based poet Chen first discovered the book with MA Hui’s poetry (published together with a biography of the Dalai Lama) prominently displayed as a bestseller in a bookstore during a visit to China in 2018. As she puts it, “I was mesmerized basically by some of the poems when I thumbed through the book, and I bought the book and I started, just for fun, translating some of those poems.”

Chen then began to publish a few of the poems in literary magazines and also to present them at literary events. People were fascinated by the poetry, and Chen was encouraged to continue with the translation.

The 70 poems that make up I Have Forsaken Heaven & Earth are divided into sections reflecting the four elements – earth, water, fire, and air – considered by Buddhists to be fundamental components of the universe. Each section opens with a painting by former Edmontonian and Chinese Canadian artist Mozhi Chen, whose art also graces the cover of the book.

The numerous Mandarin translations of Tsangyang Gyatso’s work attest to the poet’s popularity among the Chinese. “The sixth Dalai Lama was a kind of legendary figure; he was obviously a historical person, but there were stories circulated about him mostly for two things: he was a poet famous for writing love poems, and there was a kind of conflict between his love for women and his love for poetry versus his religious and political roles in Tibet back then in the 17th century,” says Chen.

“And secondly, his contribution to poetry as a genre in the Tibetan context – what he did is he wrote in a completely different style. He used the local dialect and vernacular of the Tibetan society of the region, and he kind of completely reformed the classical form of Tibetan poetry. It’s a very iconic approach to literature.”

His love poems were the main reason for his popularity, Chen says. “He is a kind of a romanticized figure, and in a sense, that is why Chinese readers are fascinated by him.”

She continues, “Even when translating MA Hui’s poetry, from the design of the book cover and the book title and the title of each individual poem, I can see how his version continued to romanticize the Dalai Lama.”

The love poems grapple with the paradoxical desire for detachment from suffering while at the same time experiencing the suffering inherent in the act of desire. This is not just the Buddhist’s dilemma, but perhaps that of every human being who ventures into the world to love at the risk of being hurt.

“There’s always tension there. It’s also reflected in MA Hui’s rewriting of the poems – you can see the tension,” says Chen.

“Which speaks to contemporary readers, and it makes sense that the book has been a bestseller in China for quite a while. It addresses the frustrations and anxieties, all these feelings of contemporary Chinese readers who are often trapped within their emotions.”