Rowan McCandless, currently the creative non-fiction editor at The Fiddlehead, is a Winnipeg writer whose short story “Castaways” was long-listed for the Journey Prize, and whose essay “Found Objects” won the Constance Rooke Creative Nonfiction Prize.

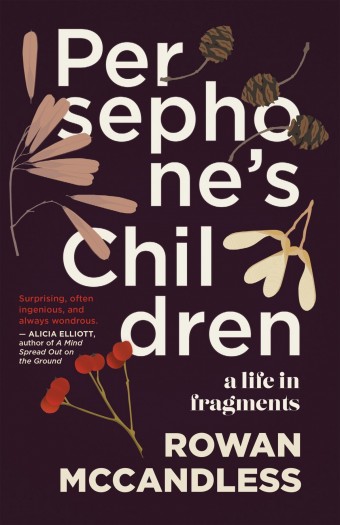

- Persephone’s Children

- Rowan McCandless

- Dundurn Press

- $22.99 Paperback, 328 pages

- ISBN: 978-14-59747-61-6

Persephone’s Children: A Life in Fragments is a memoir in the form of essays, in which McCandless looks back on an abusive domestic relationship through a variety of forms. And as a biracial woman of colour, she unravels the various threads that have made up the fragments not only of her life, but those of her ancestors.

About the title, Persephone’s Children, McCandless says, “I had always been intrigued by the myth of Persephone; how she was forced to reside in liminal spaces through no fault of her own. Persephone resonated with me as a child of a mixed-race marriage; having to negotiate through two different worlds.”

These are definitely not your grandmother’s memoirs! McCandless describes herself as a “proud creative outlier,” who weaves “traditional literary techniques with subversive forms.”

She explains: “The term outlier forms was created by one of my mentors, Nicole Breit, in 2016. It is an umbrella term for those works that push the boundaries of more traditional essays. These are the works whose structures are experimental in nature, that are often non-linear and fragmented.”

One of the forms McCandless favours is the hermit crab essay, which she describes as “a structure in which the container acts as a shell to hold the story. The term the hermit crab essay was first coined by Suzanne Paola and Brenda Miller in their book, Tell It Slant. Hermit crab essays can take the form of a list, a recipe, pharmaceutical instructions; the possibilities are endless.”

Sharing one’s story takes courage, and McCandless’s story was especially challenging. “These forms allowed me some emotional distance,” she says. “They held the perimeters of how the essays would be constructed as I wrote them. In using such structures, it became a puzzle to be solved. What form do I use to best tell the tale? What shell works best with the story? Which POV do I use? All of these considerations gave me a buffer, the emotional distance necessary to tell those difficult stories.”

The intergenerational issues are dissected in “Blood Tithes: A Primer,” while the abusive relationship is brilliantly captured in “Binding Resolutions,” the contract between McCandless and her abuser, and in “Vocal Lessons: A Diagnostic Report,” a report from a therapist looking for reasons why McCandless has lost the strong confident voice of her youth.

A crossword puzzle, a word search, a play, a teenage assault rendered as archaeological field notes – these are only a few of the ways in which McCandless examines her life. In the essay “Thoughts on Keeping a Notebook,” McCandless describes the steps in considering a notebook, first as a betrayer of secrets, and finally as the catalyst in finding a writing community that allows her voice and talent to blossom.

With the outlier forms, McCandless says she “finally discovered my voice and a way into crafting essays. It reminded me of the freedom of expression and improvisation held in Jackson Pollock’s paintings and John Coltrane’s music.”