Jeanne Randolph’s latest book, My Claustrophobic Happiness, is a satire that, in keeping with her ongoing artistic and intellectual projects, skewers capitalism and “mock[s] consumerism whenever possible.”

- My Claustrophobic Happiness

- Jeanne Randolph

- Arbeiter Ring Publishing Ltd.

- $18.00 Paperback, 104 pages

- ISBN: 978-19-27886-41-0

My Claustrophobic Happiness centres on La Betty, who believes that materialism is her calling. Randolph, a Winnipeg-based author, artist, and psychiatrist, says La Betty “is the obverse of St. Anthony of the Desert (251–356 CE). The temptations of St. Anthony are an artist’s treasure trove. His biography depicts in lurid detail every demon, phantasm, shape-shifter, anti-Christ, temptress, and sprite that assailed him as he sat naked in a cave in Egypt.

“So as I was reading Athanasius’s fourth-century biography of Anthony, it occurred to me to ask, ‘What is the 21st-century equivalent of this extremist?’”

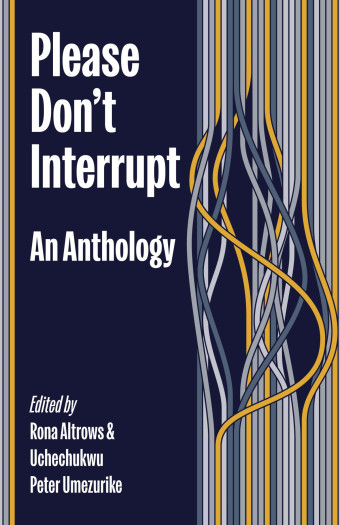

The book is structured around a series of vignettes wherein La Betty’s meditations on various luxury objects are intruded upon by various perverse interruptions.

Whether these interruptions take the form of echoes of old myths and traditional stories or whether they are reminders of social movements and values outside those of La Betty’s condo and collections of objects, she identifies them and banishes them with various advertising slogans.

“Advertising agencies are doing their best to create characters with rudimentary stories you can’t forget,” notes Randolph. “Myths, however, offer a variety of conclusions about life and how to interpret it. Advertising offers only one conclusion – ‘If you buy this you will be happy.’”

However often La Betty dismisses the old myths and the humanistic echoes of the past, Randolph contests the notion that they are defeated by her dismissal.

“The actual old myths,” she says, “belong to a complex cultural tradition in which battle, nature, and strict social mores predominated. Our technological predicament is not a tradition; it is presented as our material reality. There are no strict social mores in North American life, and battle is virtually virtual (gaming) and an ordeal foisted upon the underclass.

“As to why the old myths seem unable to stand up to slogans, maybe they do when alluded to, especially in song lyrics. Maybe they recur as metaphors.”

Randolph reveals consumerism to be ridiculous in part by leaning into the distortion caused by the clash between weighty mythical and moral interruptions – from Midas to the Green Man, from mental illness to the racist underpinnings of consumerism – and the sterile, “freeze-dried” language of advertising.

She illustrates what this attentiveness to distortion might produce with an anecdote from her childhood.

“My mother was relaxing in a rocking chair on the veranda. Some misguided neighbour had given me a fake cheerleader’s baton with sparkling grit glued all over the ball end,” Randolph recalls. “Rage impelled me to push the baton under the rockers. I became fascinated by how splintered, mashed, fragmented, yet still glittering this object became. The process was magical. It was a metamorphosis!

“My mother yelped, ‘Jeanne, you are so destructive,’ which did not seem to me at all pejorative.”