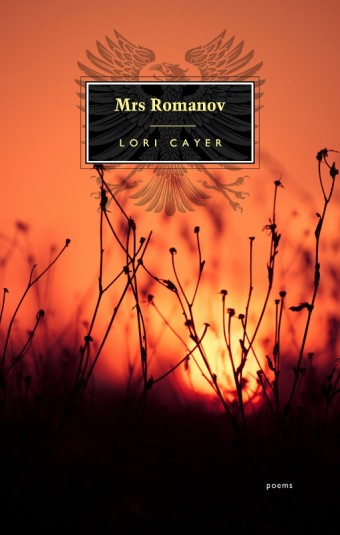

Winnipeg poet Lori Cayer’s latest book focuses on an unlikely subject: the last tsarina of Russia, Alexandra.

Mrs Romanov reads like a memoir in verse, from Alix’s marriage to the future tsar, Nicholas, to the birth of her children and her relationship with Rasputin, to the time her world came crashing down. Alexandra and her whole family were executed in a town in Siberia in 1918.

Cayer admits to feeling some connection to this woman who died exactly 100 years ago.

- Mrs Romanov

- Lori Cayer

- Porcupine’s Quill

- $16.95 Paperback, 112 pages

- ISBN: 978-08-89844-17-9

“Myinterest in her started as that of a mother of a hemophiliac being fascinated with another mother who was trying to manage this incurable disease in a time when there was no medication or treatment,” she says.

“As I learned about her I became deeply interested in her as a woman, mother, and empress who had money, privilege, and every modern opportunity, and yet she could do nothing but stand by and hope her son would live to adulthood to take the throne.”

Cayer did considerable research, reading biographies of the family and Rasputin; histories of the Romanovs, the autocracy, the revolutions; memoirs of their entourage and family members and of their commandants; scientific papers and books about their remains and identification.

_800_806_90.jpg)

“I got a good feel for her as a person from reading what diaries and letters have survived and been printed,” she says. “The family burned most of their private papers while in captivity but much can be learned by [reading] the writings of others who were around them.”

“My research took me into the depths of her marriage, her religious zealotry, and her political meddling through to World War I and the revolution. I could happily spend the rest of my life continuing to read about these people and Alexandra in particular.”

Mrs Romanov is written in the imagined voice of the tsarina, and most of the poems take the form of couplets. Cayer explains why she chose this form.

“I liked the old-fashioned look of it,” she says, “and it made sense to use it because I was writing from a perspective of excerpts, like you might find in diary entries or letters.

“It fit the way I was using English, or rather recreating her actual voice.”

“What gave me my perspective was locating the voice of a woman whose concerns are still shared woman to woman with the experience of women 100 years later.”

The second half of the book takes place after the abdication and revolution, when the family was under house arrest, and the style of the poems changes to reflect that. These poems have the headers “The Rule” and “The Light.”

“Visually they look like blocky lists, lines close together, and to me represent fists or official notices,” Cayer says. While Cayer developed Alexandra’s voice through reading both primary and secondary sources, her understanding of the person goes deeper.

“I did give her a voice,” Cayer says, “and it is a voice very like her own real voice in writing. I extrapolated from her writings and my research, but what gave me my perspective was locating the voice of a woman whose concerns are still shared woman to woman with the experience of women 100 years later.”