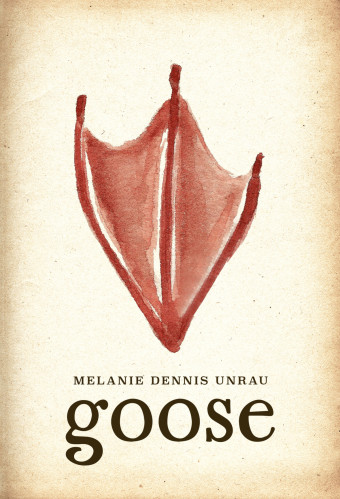

Melanie Dennis Unrau’s imaginative and incisive poetry collection Goose retraces the steps of Sidney Clarke Ells, the self-proclaimed “father of the tar sands,” by literally tracing the text and images from Northland Trails, his book of short stories, poems, illustrations, and essays published in 1938.

- Goose

- Melanie Dennis Unrau

- Assembly Press

- $22.95 Paperback, 128 pages

- ISBN: 978-19-98336-21-0

Recontextualizing and reinterpreting Ells’s archive, Goose flies in the face of settler-colonial narratives, giving voice to the land and labourers Ells exploited in his work and writing.

“This book started with the idea that Ells may have liked to think of himself as a goose,” the Winnipeg poet says.

“Geese feature more than any other non-human creature in Northland Trails. They represent him, an occasional northern resident who migrated between Ottawa and Fort McMurray and who was known for his discipline and his abrasive, loud personality (his honking, if you will).

“But the geese are also real geese who exist without and beyond Ells, so detaching them from the stories, sentences, and settings Ells puts them in allows them to trouble, exceed, and diverge from Ells’s intentions for them.”

Unrau accomplished this “detaching” by selecting words and images from the 1956 edition of Ells’s book and tracing them onto thin sheets of paper in new combinations and configurations, transforming Northland Trails into a powerful critique of past and present environmental and human destruction.

A foreword from the McMurray Métis centres the Indigenous presence that defies Ells’s efforts and claims. In Northland Trails, Ells tells of how he “helped” a team of Métis and First Nations trackers (fur-trade–era labourers) tow a boatload of tar sand along the Athabasca River from Fort McMurray to Athabasca.

“Ells knew how to make himself sound like a hero and the labourers sound incompetent, but that is only one way of telling the story,” Unrau says.

She decided to find a counternarrative. “I had the privilege this year of visiting the McMurray Métis and meeting three Elders, Frank LaCaille, Leonard Hansen, and Harvey Sykes, who have worked on the Athabasca River and who could speak to a Métis perspective on the river and to what tracking would have been like,” Unrau says.

“I am so grateful to open Goose with a foreword that celebrates and foregrounds Indigenous perspectives on the river, the trackers, the land, and the tar sands.”

While Ells portrays northern Canada as empty and primitive, Goose evokes a storied landscape.

“The land is already there in Northland Trails, making itself known and having its own things to say. It’s not containable in the ways Ells wants it to be,” says Unrau.

“For example, [in Goose] I work with one of Ells’s illustrations that has a banner celebrating the colonial impulse to conquer ‘Canada’s Last Great North.’ I omit everything but the embedded word No to highlight the land’s resistance to colonization and extraction.”

Deconstructing Ells’s record of Canada’s oil-sands industry and himself as its founder, Goose provokes readers to ask, as Unrau does, “What is Ells saying about himself and his relationship to the things he writes about and draws? And what is my relationship to those things?”