Canadian Confederation was scarcely a concept in the late 18th century when the effects of the American Revolution triggered a migration of Loyalists to Nova Scotia. With them, they brought their families, their values, and their chattel – which included Black slaves.

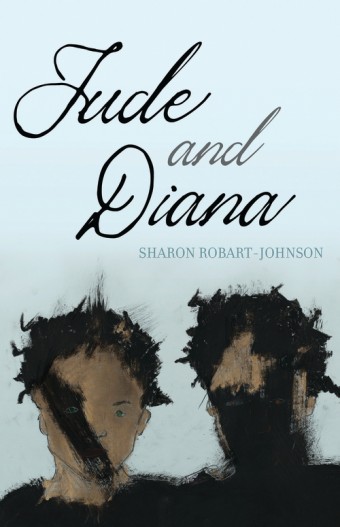

- Jude and Diana

- Sharon Robart-Johnson

- Fernwood Publishing

- $22.00 Paperback, 300 pages

- ISBN: 978-17-73634-41-8

Before writing a fictional account of this era, Sharon Robart-Johnson, a 13th-generation African Nova Scotian and researcher of slavery, had been working on her history book, Africa’s Children: A History of Blacks in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. Her meticulous research uncovered the story of a slave named Jude who died at the hands of her owners and the sensational trial that followed.

“When I first discovered those court records and read every single word, I can’t begin to tell you how angry I was,” Robart-Johnson says. “I was as ignorant as the next person as to what went on in our little town.”

She knew then that she would have to try to tell Jude’s story – what her life may have been like before she became the property of Major Andrews (Anderson in the novel) and his family. Because court records state that Diana was her sister, Robart-Johnson also needed to include what her life would have been like. Because there was no information about Jude other than her death and the trial, another history book was out of the question.

“Therefore,” says Robart-Johnson, “I combined as much fact as there was with fiction and wrote a novel.”

Jude and Diana opens with a note from Roseway Publishing that highlights the collaborative nature of the editorial process. The publisher notes that the novel contains references and language – “the N-word and other racist language colloquial to the time” – that raises ethical considerations.

The publisher also states, “we believe the author has the right . . . to historical accuracy – inasmuch as that is possible, considering white colonizers deemed Black lives unnecessary to document.” The explanation goes on to describe how the publisher and Robart-Johnson worked together to mitigate any harm such words might cause.

Robart-Johnson had already researched how slaves spoke when she first decided to write the novel, having come across 17 volumes of narratives of slaves from Alabama to Virginia.

“Some of their narrative was extremely hard to read,” she says. “Therefore, I chose to use the words of some of the slaves that anyone who read my book would be able to read. My editor wanted to keep it as authentic as possible.” The book includes reference information about where those slave narratives can be found.

Robart-Johnson wants people to read what happened to Jude and “to be as outraged as I was by the fact that her killers got away with murder despite the overwhelming evidence given in the testimonies of Yarmouth’s coroner, Nehemiah Porter, and Yarmouth’s surgeon, Dr. Joseph Norman Bond.”

Robart-Johnson wants readers to question how that great injustice could have happened.

“I also want them to feel compassion for these two young women whose lives ended in such a heinous way,” she says.

“Jude and Diana may be gone, but their voices will ring loud and clear with my book.”