Do you believe in ghosts? In Winnipeg a century ago, that was no idle question, but rather the subject of dedicated scientific study.

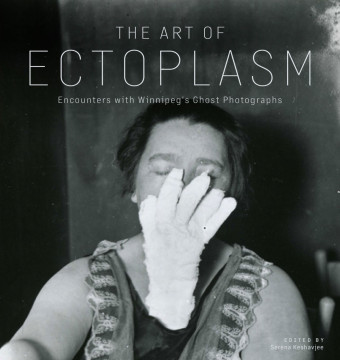

- The Art of Ectoplasm

- Serena Keshavjee (Editor)

- University of Manitoba Press

- $34.95 Paperback, 328 pages

- ISBN: 978-17-72840-37-7

Along Henderson Highway in Elmwood stands Hamilton House, so named for Dr. Thomas Glendenning (T. G.) Hamilton, who lived there with his wife Lillian and family in the 1910s to 1930s, and where he conducted research into psychic phenomena.

His and his wife’s work, thoroughly documented in photos and writing, is the subject of a new collection of essays, The Art of Ectoplasm: Encounters with Winnipeg’s Ghost Photographs, edited by Dr. Serena Keshavjee, who currently teaches modern art and architecture at the University of Winnipeg.

Central to the book, and to Hamilton’s research, are a vast collection of photographs taken during seances showing ectoplasm flowing from mediums’ mouths and noses; faces of the dead; and tables tipping or flying into the air apparently by themselves.

Hamilton devised a technologically sophisticated array with up to 11 cameras to capture images by remote control. The events were regularly observed by outsiders with a critical eye, and mediums were physically examined before the seances. Luminaries such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle attended. After T. G. Hamilton died in 1935, Lillian continued the work until 1944.

As an art historian, Keshavjee was drawn to the photos’ aesthetic. “Their clarity, their focus on the female figure with this beautiful, organic-shaped ectoplasm, the cropping, the black-and-white contrast, all of this fits the paradigm of modernist photos,” she says, adding they were not created as art but as scientific illustrations.

She first came across the Hamilton photos in 1997 while searching for French spiritualist photos. “The quality was incredible,” she says.

Keshavjee notes that the photos, many of which are reproduced in the book, were difficult to discover until the University of Manitoba Archives Special Collections digitized them, opening up access to a much wider audience. Archivist Shelley Sweeney contributes an essay about this digitization.

The book’s other contributors – Essylt Jones, Katie Oates, Walter Meyer zu Erpen, Brian Hubner, KC Adams, Murray Leeder, and Keshavjee herself – examine various aspects of the Hamiltons’ work.

They consider the context of the First World War and the influenza pandemic – which killed the Hamiltons’ three-year-old son – the gendered nature of scientific research, and the contribution of this body of work to Winnipeg’s reputation for weirdness. Consideration is given to how one can evaluate the veracity of fantastic events or appearances, as well as the changing understanding of science over the decades.

“This was ‘alternative science.’ That’s the most generous term, that was still acceptable within orthodox scientific circles,” says Keshavjee, adding that Hamilton was not ostracized for his psychic research, which attracted international attention.

Whether Hamilton’s work is evidence of ghosts, documents intangible phenomena, or illuminates a society grappling with loss, is ultimately up to the reader to determine. But one thing is clear: a century later, these photos still have the power to fascinate.

Keshavjee notes this is likely one of the reasons why Hamilton’s work has inspired contemporary artists, including filmmaker Guy Maddin.

“They’re uncanny, they’re compelling – we might describe them generally as kind of surrealist.”